**** Info via Environment Canada

Fall season outlook via Environment Canada

Meteorologically-speaking, summer has already wound down and fall is officially upon us! It’s time to start preparing for sweater weather, colourful and crunchy leaves, and pumpkin spice with everything nice.

Meteorological fall is the transition between the warmest season (summer) and the coldest season (winter). It officially begins September 1 and ends November 30.

Let’s have a look at what the fall has in store for us:

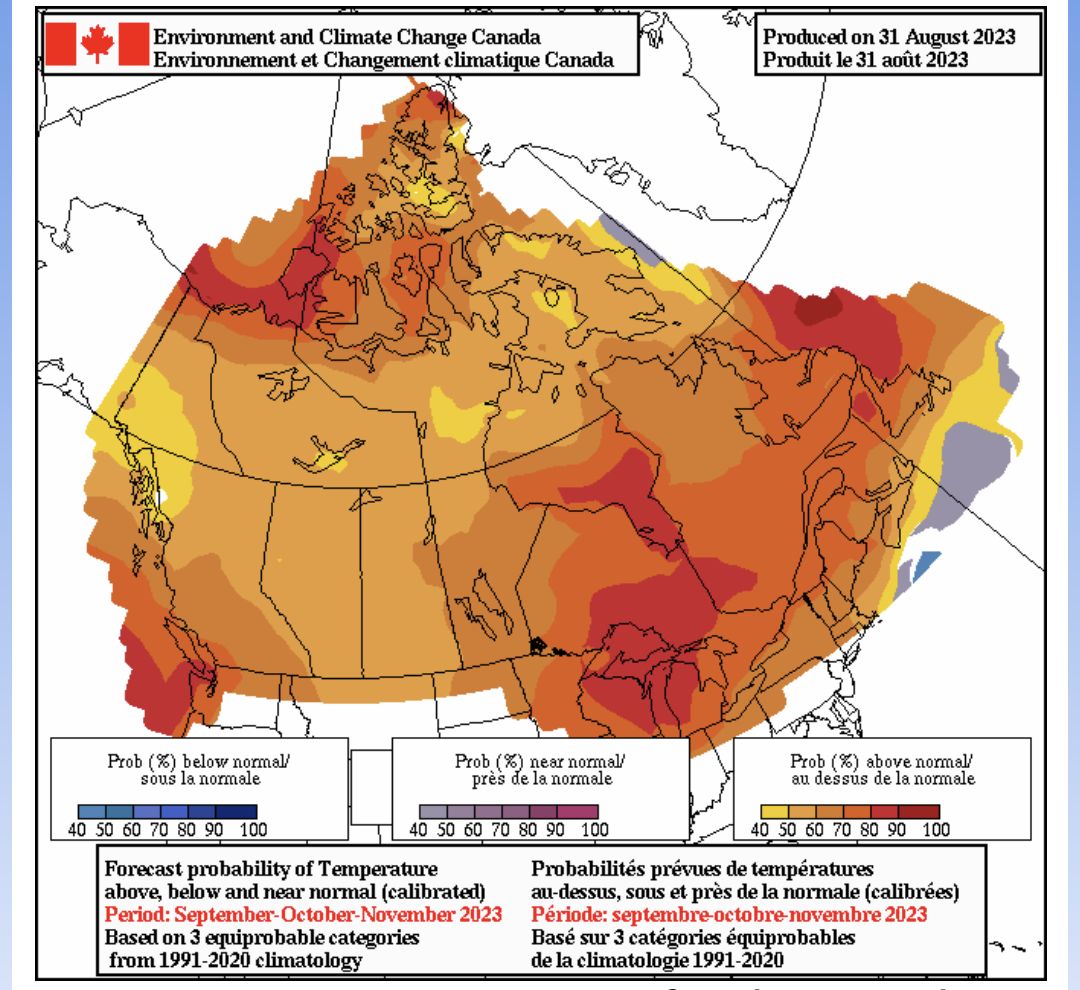

Average temperatures map for the months of September, October and November. As we can see, over the next three months, there is a relatively high probability that most of Canada will experience above-average temperatures.

Warm conditions across most of the country are expected to persist for the upcoming fall. Coastal British Columbia, the high Arctic, and Atlantic Canada can expect consistently warmer-than-usual conditions. The current El Niño event is expected to be strongest in late fall and then weaken into winter and spring. This could lead to cooler conditions in Eastern Canada and warmer conditions in Western Canada.

In August, NOAA revised their hurricane forecast, projecting heightened activity. This is attributed to exceptionally warm ocean surface temperatures, which are offsetting the usual hurricane formation limiting effect of El Niño. Just this week, the Canadian Hurricane Centre started monitoring hurricane Lee, which has become the 13th named storm of 2023. As a comparison, the average at this time of year is normally seven named storms.

Recap on this summer

The world just experienced the hottest summer on record and Canada was no exception, as large parts of the country experienced above-average temperatures over the season. However, Baffin Island and parts of Eastern Canada (central and southern Ontario, southern Quebec, and parts of the Maritimes) had near-normal to below-normal temperatures this summer.

Temperature anomalies (difference from normal) for the summer season (June, July, and August).

An upper ridge that lingered over western Canada and the western Territories this summer caused the warm and dry weather in these regions, blocking moisture and maintaining high temperatures. These persisting hot and dry conditions only helped to fuel the already raging forest fires. The total area burned this summer (close to 17 million hectares) already represents more than double the historic record in one season, 7.6 million hectares, previously set in 1989. This year’s wildfire season has burned further, faster and is predicted to last longer than any season in the past.

In terms of rainfall, eastern Canada had an unusually wet summer with much more precipitation than normal. However, in many other parts of the country, there was much less rain than normal, making existing drought conditions even worse.

Precipitation anomalies (difference from normal) for the summer season (June, July and August).