**** Info via Environment Canada

WILDFIRE SEASON – EARLY, ACTIVE AND Unrelenting 2021

Across Canada, the wildfire season started about a month early, due to the record dry spring and early loss of alpine snow. Nationally, the number of fires was 2500 more than in 2020 and the area of woodland burned was 1.6 times the 10-year average.

In British Columbia, wildfires started up in late June and continued into September. The BC Wildfire Service reported 1522 fires that scorched 889 813 hectares of timber, bush and grassland – an area 1.5 times that of Prince Edward Island, almost 60 times the area burned in 2020, and the third most ever. Fires were often fast moving and aggressive which prompted 50 000 evacuations and a province-wide state of emergency for the third year out of the last five. British Columbia fire crews were supplemented by others from across Canada, Mexico and the Canadian military, totalling 5300 wildfire fighters.

In addition to the human losses and property, fires killed millions of wild animals and destroyed wildlife habitats, and generated smoke that was carried both to the South Coast and east across the Rockies. Often in the path of forest fires this summer, Kamloops experienced a record 478 hours of smoke and haze.

On July 10, fires were out-of-control in every province and territory except for Atlantic Canada and Nunavut. In Prairie big sky country, skies were often eerie-grey-orange and you couldn’t see across the street. Calgary recorded 512 hours of smoke and haze (normal yearly count is 12 hours) – the dirtiest skies in 70 years of record keeping. At the Calgary Stampede, horseracing and chuckwagon races were cancelled over safety concerns for animals, participants and spectators.

In Northwestern Ontario, hot and dry weather in spring and summer contributed to devastating fire conditions. There were 50% more forest fires compared to the 10-year average, but they burned five times the average area burned in a year. The Province of Ontario called it the worst forest fire season on record, surpassing the previous record in 1995 by 10%. Ontario imposed restrictions on mining, rail, construction and transportation activities in order to reduce the likelihood of sparks igniting more fires. More than 3000 evacuees from Ontario First Nations communities were relocated with an added 5000 people on short-notice alert.

.

CANADA DRY COAST TO Coast 2021

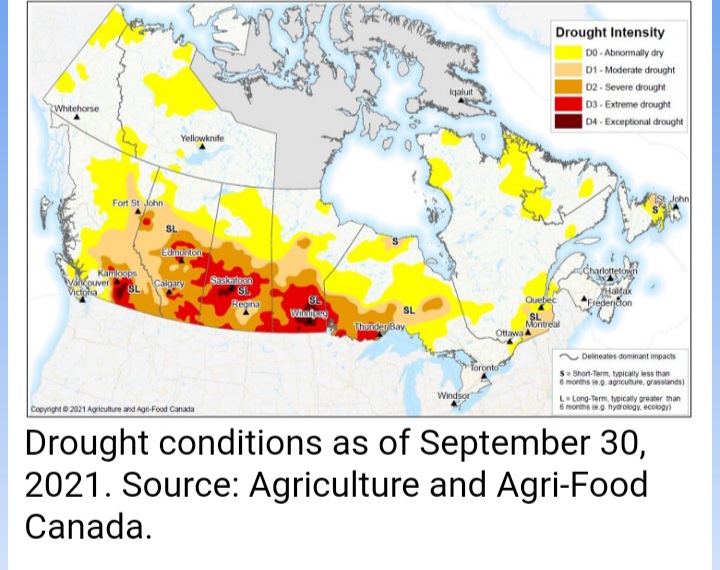

Veteran farmers and ranchers don’t hesitate to call this year’s drought across Western Canada one of the worst in history. Farmers compare it to 1988 and 1961; historians compare it to the 1930s. What made the drought extraordinary was that the dryness was so widespread, severe and long-lasting. Even before summer was half over, dozens of rural communities had declared states of agricultural disaster. With a week to go before harvest, the Canadian Drought Monitor classified 99% of the Prairies agricultural landscape as a drought scene.

The lack of summer rains in the west contributed to the searing heat and spreading wildfires. Persistent blocking ridges redirected the jet stream farther north keeping water-bearing clouds from forming. As a result, southern regions between British Columbia’s Lower Mainland and Interior to Northwestern Ontario faced one of their driest summers in 75 years, with many places recording less than half their normal rainfall during the growing season.

However, the seeds of this drought were sown months, if not seasons, before 2021. Across much of the west, fields through winter 2020-21 were brown for more days than they were white with snow. Winter had not been this dry in 50 years in parts of Alberta. Edmonton had its second driest winter in 136 years. In Calgary, the spring rain was less than half of normal. Southern Manitoba was Canada’s epicentre for drought, especially in the Red River Valley and the Interlakes region. Some places like Winnipeg had their two driest back-to-back years in over a century.

Some cities began worrying about running out of drinking water. The Red River flow at Emerson fell to 50% below normal. In parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan, the gumbo clay soil was so dry and shifting that home foundations began cracking and settling. When the later rains came so did the leaking.

August rains came too late to help the cereals and canola although they did help later-producing crops such as corn, soybeans, potatoes and sunflowers. The impact of the drought on food producers across the Prairies was devastating. Compared to other agricultural drought years, the economic loss from this year’s dryness was easily into the billions of dollars, and all Canadians felt the impacts of the drought through higher food prices.